As he once put it, “The child asks, ‘Why don’t I have this happiness thing you’re telling me about?’” His own up-by-the-bootstraps childhood was marked by insecurity and self-doubt. Silverstein detested stories with happy endings. His biography and body of work suggest a subtler, and, in the end, perhaps an even more troubling, way of looking at it. Still, it’s difficult to know whether Silverstein, who died of a heart attack in 1999, after keeping out of the public eye for more than two decades, meant for us to read the book so conclusively. William Cole, who turned down the manuscript when he was an editor at Simon & Schuster (Silverstein took it to Harper & Row), was troubled by its portrayal of parenthood: “My interpretation is that that was one dum-dum of a tree, giving everything and expecting nothing in return.” More recently, the children’s-book author Laurel Snyder said, “When you give a new mother ten copies of ‘The Giving Tree,’ it does send a message to the mother that we are supposed to be this person.”

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, environmental activists rue the boy’s pillaging of the tree and, by extension, the environment. One blog post, “ Why I Hate The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein,” argues that the book encourages selfishness, narcissism, and codependency. “The Giving Tree” ranks high on both “favorite” and “least favorite” lists of children’s books, and is the subject of many online invectives. She is likewise “happy” to give him her branches, and later her trunk, until there is nothing left of her but an old stump, which the old man, or boy, proceeds to sit on.Ī little Googling corroborated my own distaste. Not having any to offer him, the tree is “happy” to give him her apples to sell.

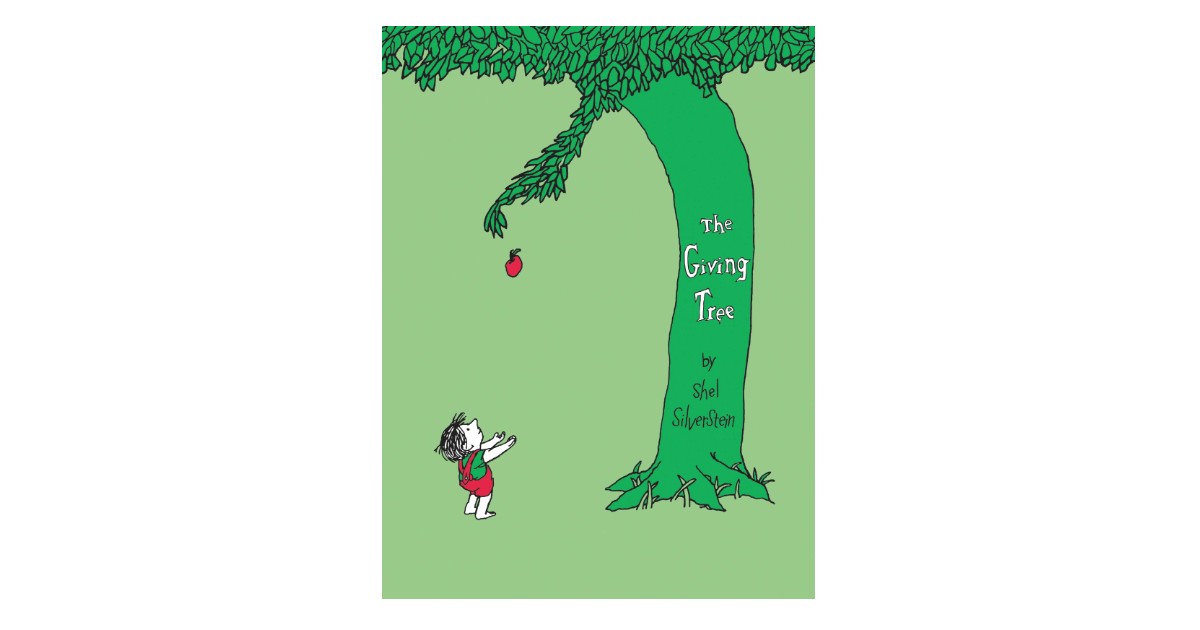

One day, the boy, now a young man, returns, asking for money. But then time passes, and the boy forgets about her. “And the tree was happy,” goes the refrain. The beginning of the story is innocuous enough: a boy climbs a tree, swings from her branches, and devours her apples (I’d never noticed that the tree was a “she”).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)